Jim Freeman and Greg MacGillivray were two young Southern California filmmakers who made their significant cinematic forays in the mid-‘60s when the surf-film rage was just beyond its peak. The early kings of the medium were Bruce Brown, John Severson, Bud Browne and a long list of also-rans. “The raunchiest crowds in surf film history were back in the early’60s,” Greg recalls, “especially for the low quality films—and there were plenty of them. There were about 12 films a year in those days, and nine of ‘em were made by rip-off artists and sure to be terrible. I saw them all.”

about 12 films a year in those days, and nine of ‘em were made by rip-off artists and sure to be terrible. I saw them all.”

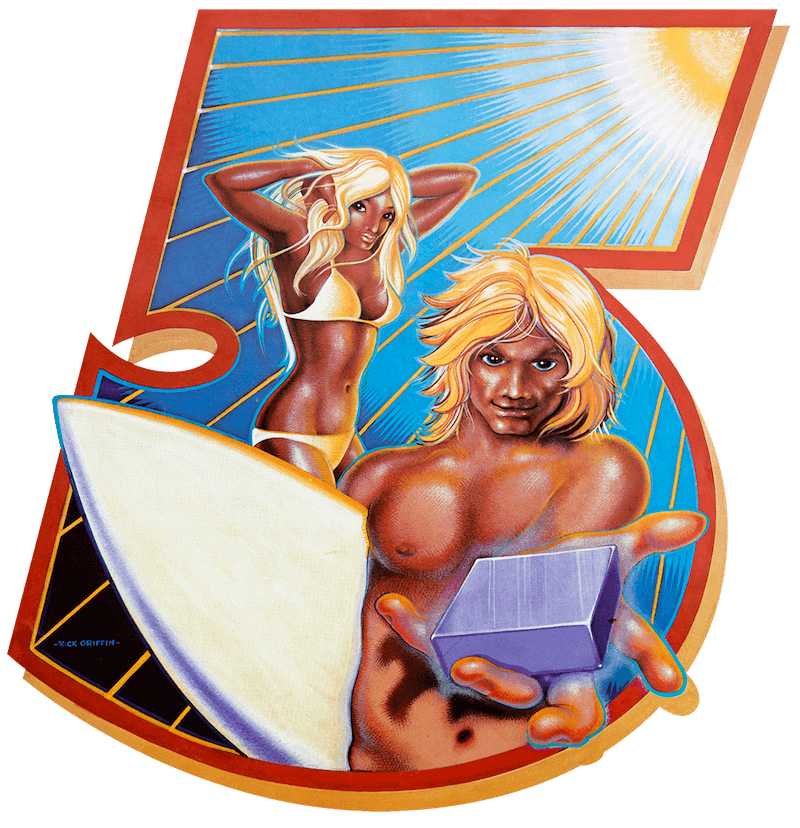

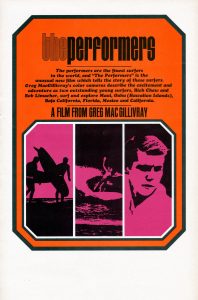

Greg MacGillivray grew up in the Newport-Laguna Beach area, and his twin loves were always surfing and movies. At 14, he combined the two, entertaining his surfer friends with funny, well-photographed 8mm films of the local action. Greg began his first professional film in high school, and after 31/2 years of work, he released A Cool Wave of Colorduring his freshman year in college. A year later, he premiered The Performers.

Jim Freeman was from Santa Ana and, although he was never mush of a surfer himself, he had a genuine appreciation for this ubiquitous Southern California saltwater dance form. His interest in filmmaking eventually led him to a series of surf flicks, including The Glass Wall, Let There Be Surf and, most notoriously, the only 3-D surf movie, Outside the Third Dimension.

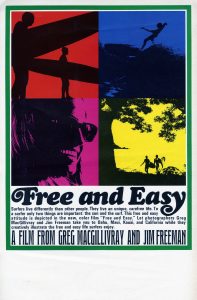

Freeman and MacGillivray decided to throw in together in 1965. “We both had ideas that required using two cameras simultaneously, one from the beach and one from the water, and we could only do that together,” MacGillivray remembers. The instant and phenomenal success of their first collaboration, Free and Easy, proved that two heads were better than one. Released in 1967, Free and Easy used the first slow-motion “organic” water photography to reveal the color, fluidity and dance-like beauty of surfing.

Freeman and MacGillivray decided to throw in together in 1965. “We both had ideas that required using two cameras simultaneously, one from the beach and one from the water, and we could only do that together,” MacGillivray remembers. The instant and phenomenal success of their first collaboration, Free and Easy, proved that two heads were better than one. Released in 1967, Free and Easy used the first slow-motion “organic” water photography to reveal the color, fluidity and dance-like beauty of surfing.

The dynamic duo’s Waves of Change(1969) broke new ground, too, chronicling the changing trends in surfing with the industry’s first use of super-slow-motion photography.

The dynamic duo’s Waves of Change(1969) broke new ground, too, chronicling the changing trends in surfing with the industry’s first use of super-slow-motion photography.

But success breeds success, and MacGillivray-Freeman’s exceptional camerawork did not go unnoticed in nearby Tinseltown. The company began to attract a broad range of work, from commercials for national television to major motion-picture involvement (Jim’s extraordinary heli-cam work for Jonathan Livingston Seagull and Greg’s wonderful panoramas for Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining illustrate their level of expertise).

So it was that the two decided to leave their surf-film days behind. There was just too much artistically challenging work to do, and it seemed like they’d done just about everything that could be done with surfing. Almost.

The Making of Five Summer Stories